Great Awakening

Sunday Morning in Old Virginia-Bruton Parish Church, Williamsburg, Virginia-1760

While some colonists came to America seeking freedom from religious persecution, others had never experienced religious persecution, and they were perfectly happy with their officially established Anglican faith, and its mother church the Church of England. However, no matter what their denomination was the average colonist typically wanted their religion to dominate over the others.

By the year 1750, there were 1,500 local congregations in Colonial America. At this time it was estimated that 2/3rds of the adult population attended church. The largest denomination was the Congregationalist (Puritan) with 450 churches. Almost all of Puritan churches were in New England. The Anglican Church (Church of England) was second with 300 churches. They were mostly in South and North Carolina. Next came the Quakers with 250 meeting halls, followed by the Presbyterians with 160 churches, most of which were found in the middle colonies. Colonists were required to pay taxes in support of their local church. Churches were also used for social and political gatherings and holding elections.

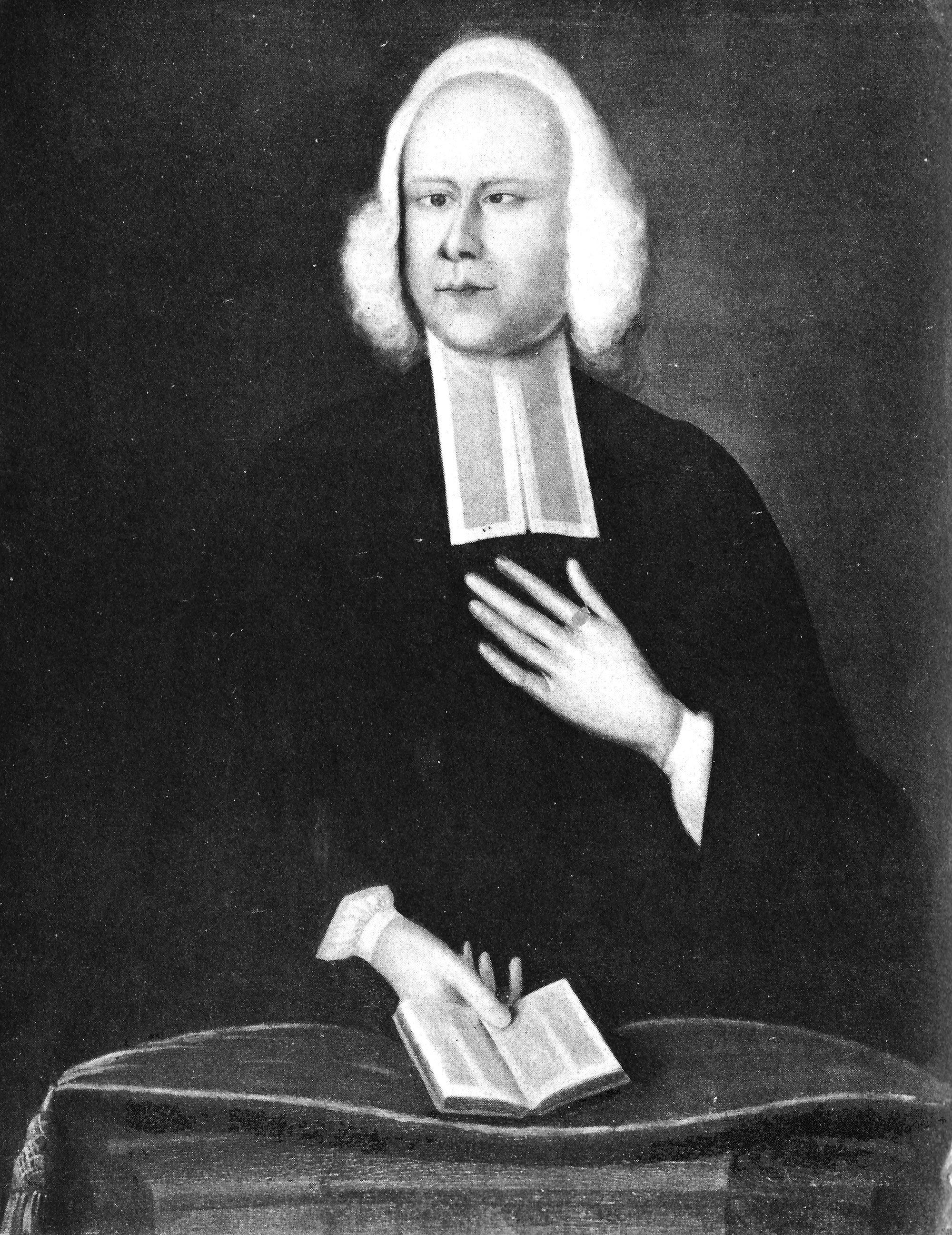

George Whitefield

During the mid-1700's, British Colonial America became engulfed in religious revivals that collectively became known as the Great Awakening. The revivalists emphasized a religious conversion that transformed sinners into saints, while providing eternal salvation. The revivalists believed that only God's grace could save the sinner. It was the job of the evangelical preacher to take a seeker through the dept of despair and then pull them into an ecstatic experience of divine grace. Energetic ministers preached sermons that shocked the parishioner into recognizing that they were headed to impending “Hell.” At the same time they told them that if they sought salvation they could find eternal joy in heaven. They called this movement “New Birth.”

In 1737, Reverend Jonathan Edwards, whose family led the revivalist movement wrote a book that guided future revivals. It was called, “A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God.” In the book, Edwards richly details how God had worked throughout the colonies. He also provided models of preaching and conversion. The book was widely received in England where it was read by a young Anglican priest named George Whitefield. Whitefield had developed his own evangelical style that was now at odds with the Church of England. Whitefield is described as a charismatic speaker, who spoke without notes. He commanded his audiences with vocal control. As he spoke he made dramatic movements leaving the parishioners to believe that it was God who was speaking. Before long, Whitfield was touring Whales and England where he began to draw crowds that were too large to fit into a church. He converted thousands in the streets, in parks, and in fields.

Then in 1739, Whitefield became very popular in the colonies as the newspapers reported his success in Europe. Soon afterward, Whitefield crossed the Atlantic Ocean for a 14 month evangelical tour. The tour ran from Maine to Georgia. During the tour George visited Philadelphia where he met Benjamin Franklin and the two became very close. At the time Benjamin Franklin was the leading writer, publisher, and social reformer in the colonies. Franklin published everything Whitefield had to say in his Pennsylvania Gazette, and his issues sold like wildfire. Between 1739 and 1745, over 80,000 copies of Whitefield's publications were published in America, or about 1 copy for every 10 people who lived in Colonial America. George Whitfield's final sermon was in Boston where he drew 20,000 people, more than the entire population of the city at that time.